|

Basic Call to Consciousness

Intention

Invented White

History & Imagery

In the Beginning

First Nations Governance

Trail of Tears

Tragedy of

Little Bighorn

Massacre at

Wounded Knee

Duwamish/Suquamish

Displacement

Cultural Genocide

Native Values

Impact of European Immigrants

The Take-over

Called ‘Indian’ or....

Cultural Genocide - Boarding schools

Native Values &

Way of Life

Morality

Depression &

Substance abuse

Cultural Distinctions

Spiritual Sensibilities

Language

Living Two Lives

Leaders or Rulers

Written or Oral

Painful History

Iroquois Conservation

Chief Seattle’s

Farewell Speech

Spirit Road

|

|

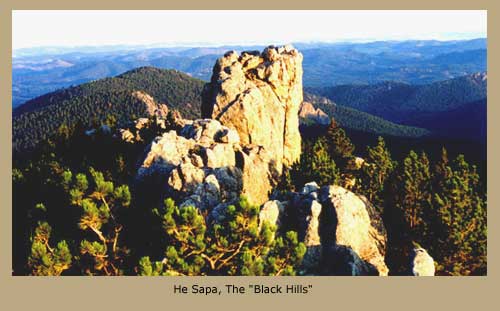

Tragedy of Little Bighorn 1876

In Lame Deer Seeks a Vision, he explains the true nature of the conflict between First Nations and the U.S. government.  The Battle of Little Bighorn, 1876, in the Black Hills of South Dakota, sacred landscape of the Lakota, Cheyenne & Omaha people. Books, film and media had portrayed Custer’s battle there with sympathy for Custer and his men. Little to no attention has been paid to the true nature of this conflict; the focus is most often on the war, itself, not on the true instigation of this grand loss of lives. Once again, the U.S. government promised land treaties with First People, this time the Lakota bands, and, later, without conscience, broke the treaties when natural resources were found in their sacred hills. Here is the history of this conflict. In the Black Hills, four thousand archaeological sites spanning 12,000 years attest to a long relationship with Native People. An oblong ridge circles the Black Hills, separating them from the surrounding prairie grasslands and making them one of the most unusual environmental features in the United States, according to anthropologist Peter Nabokov. In the 1700s and 1800s, the Lakota ceremonial season began each spring. The Lakota believe that permanent occupancy of the Black Hills was set aside for the birds and the animals, not for humans. To them, the landscape was sacred. It was also home to the burial grounds of their ancestors. The Battle of Little Bighorn, 1876, in the Black Hills of South Dakota, sacred landscape of the Lakota, Cheyenne & Omaha people. Books, film and media had portrayed Custer’s battle there with sympathy for Custer and his men. Little to no attention has been paid to the true nature of this conflict; the focus is most often on the war, itself, not on the true instigation of this grand loss of lives. Once again, the U.S. government promised land treaties with First People, this time the Lakota bands, and, later, without conscience, broke the treaties when natural resources were found in their sacred hills. Here is the history of this conflict. In the Black Hills, four thousand archaeological sites spanning 12,000 years attest to a long relationship with Native People. An oblong ridge circles the Black Hills, separating them from the surrounding prairie grasslands and making them one of the most unusual environmental features in the United States, according to anthropologist Peter Nabokov. In the 1700s and 1800s, the Lakota ceremonial season began each spring. The Lakota believe that permanent occupancy of the Black Hills was set aside for the birds and the animals, not for humans. To them, the landscape was sacred. It was also home to the burial grounds of their ancestors.

The U.S. government, having signed the 1851 Treaty which promised 60 million acres of the Black Hills for the absolute and undisturbed use and occupancy of the Sioux--Lakota, as they called themselves, and, preventing immigrant settlement of the Black Hills. Settlers were aware that the Black Hills were sacred to Native People, considered the womb of Mother Earth and the location of their ceremonies, vision quests, and burials. Initially, the newcomers accepted the fact that the Hills belonged to the Lakota-until gold was discovered. When they heard the rumors of gold, they clamored for access to an area that had previously been avoided for fear of Native American attacks and because of the 1851 Treaty.

In 1857, Lakota leaders gathered at Bear Butte to discuss the increasing number of white invaders in the Black Hills--putting roads in their sacred hills which also disturbed the buffalo which was the Peoples' main source of existence.  This angered the Lakotas. As settlers continued to ignore the treaty boundaries of the Black Hills, as the government began building roads and military posts to assure the safety of the westward moving settlers, a second treaty was signed by only a few Lakota leaders which reduced their land base. This was the 1868 Treaty, the one to which all current legal arguments refer. In 1874, the government allowed General George Custer to explore the Hills-ostensibly to find a place to build a fort, but Custer was accompanied by geologists and miners who confirmed the presence of gold. This was a clear violation of even the second, more limited, treaty. Discovery of gold sparked a rush of miners and settlers into the sacred hills--which infuriated the Lakota--and the government tried to threaten the Lakota into selling their remaining acres. This angered the Lakotas. As settlers continued to ignore the treaty boundaries of the Black Hills, as the government began building roads and military posts to assure the safety of the westward moving settlers, a second treaty was signed by only a few Lakota leaders which reduced their land base. This was the 1868 Treaty, the one to which all current legal arguments refer. In 1874, the government allowed General George Custer to explore the Hills-ostensibly to find a place to build a fort, but Custer was accompanied by geologists and miners who confirmed the presence of gold. This was a clear violation of even the second, more limited, treaty. Discovery of gold sparked a rush of miners and settlers into the sacred hills--which infuriated the Lakota--and the government tried to threaten the Lakota into selling their remaining acres.

The area had been primarily Indian Territory, with some of its designated sacred Indian burial ground. The lure of the gold was great and prospectors did not hesitate to over-run Indian lands.

Chief, Wanigi Ska (White Ghost) stated: “You have driven away our game and our means of livelihood out of the country, until now we have nothing left that is valuable except the hills that you ask us to give up.....  The earth is full of minerals of all kinds, and on the earth the ground is covered with forests of heavy pine, and when we give these up to the Great Father (in Washington) we know that we give up the last thing that is valuable either to us or the white people.” The earth is full of minerals of all kinds, and on the earth the ground is covered with forests of heavy pine, and when we give these up to the Great Father (in Washington) we know that we give up the last thing that is valuable either to us or the white people.”

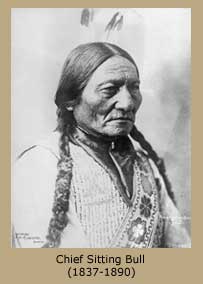

Chief Sitting Bull, 1837-1890, Hunkpapa, subgroup of Teton Lakota, a Leader and Medicine Man, a great warrior and also a spiritual leader with strong powers, was not there, but his people conveyed his warning: “We want no white men here. The Black Hills belong to me. If the whites try to take them, I WILL fight.”

Chief Sitting Bull

When the threats and bullying didn’t work, Congress enacted a new treaty in 1877 seizing the land, resulting in war and eventual defeat for the Lakota-though Custer died for his sins in 1876 at Little Bighorn. In the twentieth century, the Lakota began a concerted legal effort to reclaim the Black Hills. A federal judge who reviewed the case in the 1970s commented: “A more ripe and rank case of dishonorable dealing will never, in all probability, be found in our history.”

Sitting Bull sought refuge in Canada in 1877. Four years later, with his supporters on the brink of starvation, Sitting Bull returned to the U.S. at Standing Rock Agency in North Dakota. There, he fought the sale of tribal lands enacted by the Dawes Act and supported the Ghost Dance Movement--a cultural and religious revitalization ceremony among First Nations People. The U.S. government, threatened by a religious awakening they perceived would promise the end of white dominance, federal authorities wanted to arrest Sitting Bull in 1890 for his support of the religious movement. He was killed resisting arrest.

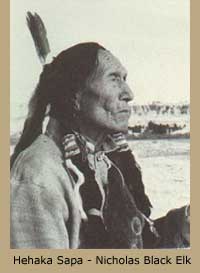

Black Elk--Lakota holy man, 1863-1950, related his story, that he was told by his grandfather:

“…the wasichus, white people, were coming and that they were going to take our country and rub us all out…that the wasichus had found the yellow metal that the European immigrants called gold that they worship and that makes them crazy and they want to put in a road up through our country to the place where the metal was; but my people did not want the road. The road would scare the bison and make them go away…Once we were happy in our own country and we were seldom hungry, for then, the two-leg-geds and the four-leg-geds lived together like relatives and there was plenty for them and for us.”

Black Elk--Lakota holy man, 1863-1950, related his story, that he was told by his grandfather:

“…the wasichus, white people, were coming and that they were going to take our country and rub us all out…that the wasichus had found the yellow metal that the European immigrants called gold that they worship and that makes them crazy and they want to put in a road up through our country to the place where the metal was; but my people did not want the road. The road would scare the bison and make them go away…Once we were happy in our own country and we were seldom hungry, for then, the two-leg-geds and the four-leg-geds lived together like relatives and there was plenty for them and for us.”

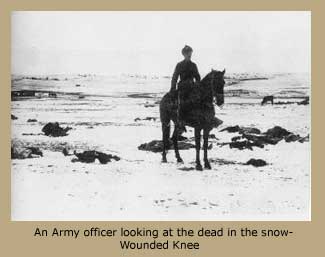

Massacre of Indian Women, Children & Men

at Wounded Knee - December 29, 1890

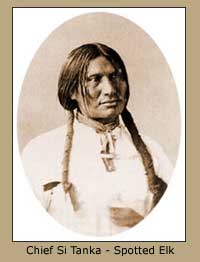

After Sitting Bull was killed--related to religious persecution, his followers fled to seek refuge with his half-brother, Chief Spotted Elk, 1815 - 1890, also known as Big Foot--Chief of the Mneconjou, a subgroup of the Teton Lakota. After Sitting Bull was killed--related to religious persecution, his followers fled to seek refuge with his half-brother, Chief Spotted Elk, 1815 - 1890, also known as Big Foot--Chief of the Mneconjou, a subgroup of the Teton Lakota.

Fearing for the safety of his band, which consisted mostly of widows of the Plains wars and their children--120 surviving men and 230 women and children, Spotted Elk was heading to Pine Ridge for support. Spotted Elk was considered a man of peace by his people--skilled at settling quarrels. Following the defeat of the Lakota in 1876, Spotted Elk had urged his followers to adapt to the white man’s ways while retaining their Lakota language and cultural traditions. Many Lakota owe their new traditions to his influence. He also encouraged his people to adapt to life on the reservation by developing sustainable agriculture and building building schools Lakota children. He had advocated a peaceful attitude toward the white settlers.

However, due to poor living conditions on the reservations--made worse by fraud and corruption on the part of Indian agents charged, by law, with supplying the tribe with basic necessities--the Lakota were in a state of great despair; by 1889, they began looking to a radical solution to their increasing suffering.

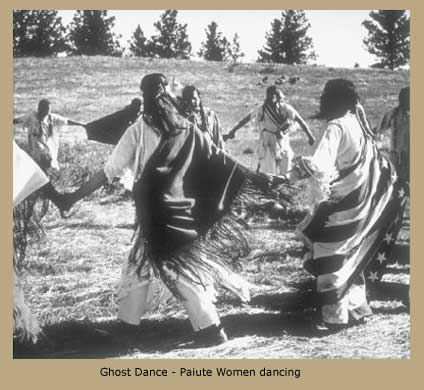

The radical solution came in the form of the Ghost Dance Religion; initiated in 1889 by a Paiute prophet named Wovoka. Spotted Elk and the Lakota were among the most enthusiastic supporters in the Ghost Dance ceremony when it arrived among them in the spring of 1890. The radical solution came in the form of the Ghost Dance Religion; initiated in 1889 by a Paiute prophet named Wovoka. Spotted Elk and the Lakota were among the most enthusiastic supporters in the Ghost Dance ceremony when it arrived among them in the spring of 1890.

In a vision, Wovoka saw the earth reborn in a natural state and returned to the Indians and their ancestors, free from white man’s control. Wovoka taught his followers that they could achieve this vision by dancing, chanting, and eliminating all traces of white influence from their lives.

Although government-imposed reservation rules outlawed the practice of the religion, the movement swept like a wild fire of enthusiasm through their camps offering a last shred of hope to an oppressed and hopeless Nation, causing U.S. government to react with alarm.

In December 1890, because he had been placed on the white government’s list of instigators of disturbances due to his support of the religious movement, Spotted Elk headed south to the Pine Ridge Reservation at the invitation of Chief Red Cloud. Red Cloud hoped that his fellow chief could help make peace. Hoping to find safety there, having no intention of fighting, and flying a white flag, Spotted Elk also contracted pneumonia on the cold winter journey to Pine Ridge.

As they neared Porcupine Creek on December 28, the band saw four troops of cavalry approaching. A white flag was immediately run up over Big Foot’s wagon; he was sick, lying in the wagon, with pneumonia. When the two groups met, Big Foot raised up from his bed of blankets to greet the Major of the Cavalry. His blankets were stained with blood and blood dripped from his nose due to his illness as he spoke.

Then the Natives were informed that they would be disarmed. Natives stacked their guns in the center, but the soldiers were not satisfied. The soldiers went through the Natives' tents, bringing out bundles and tearing them open, throwing knives, axes, and tent stakes into the pile. Then they ordered searches of the individual warriors. The Natives became very angry.

The search found only two rifles, one brand new, belonging to a young man named Black Coyote. He raised it over his head and cried out that he had spent much money for the rifle and that it belonged to him. Black Coyote was deaf and therefore did not respond promptly to the demands of the soldiers. He would have been convinced to put it down by his tribes people, but that option was not possible because the soldiers so hastily grabbed the youth and spun him around. Then a shot was heard; its source is not clear but it began the killing. The only arms the Natives had were what they could grab from the pile. When the army opened fire, shrapnel shredded the lodges, killing men, women and children, indiscriminately. The People tried to run but were shot down “like buffalo”, women and children alike. When the mass insanity of the soldiers ended, 153 dead were counted, including Spotted Elk; but many of the wounded had crawled off in the snow to die alone. However, the final death toll was estimated at 350. Later in a private letter, General Nelson A. Miles who was commanding officer had this to say:

|

“Wholesale massacre occurred and I have never heard of a more brutal, cold-blooded massacre than that at Wounded Knee. About two hundred Indian women and children were killed and wounded; women with little children on their backs, and small children powder burned by the men who killed them being so near as to burn the flesh and clothing with the powder of their guns, and nursing babes with five bullet holes through them....Col. Forsyth is responsible for allowing the command to remain where it was stationed after he assumed command, and in allowing his troops to be in such a position that the line of fire of every troop was in direct line of their own of their own comrades or their camp”- [Nelson A. Miles to George W. Baird, November 20, 1891, Baird Collection, WA-S901, M596, Western Americana Collection, The Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut.] “Wholesale massacre occurred and I have never heard of a more brutal, cold-blooded massacre than that at Wounded Knee. About two hundred Indian women and children were killed and wounded; women with little children on their backs, and small children powder burned by the men who killed them being so near as to burn the flesh and clothing with the powder of their guns, and nursing babes with five bullet holes through them....Col. Forsyth is responsible for allowing the command to remain where it was stationed after he assumed command, and in allowing his troops to be in such a position that the line of fire of every troop was in direct line of their own of their own comrades or their camp”- [Nelson A. Miles to George W. Baird, November 20, 1891, Baird Collection, WA-S901, M596, Western Americana Collection, The Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut.]

|

Black Elk sadly expresses, reflecting on the Massacre-- “I did not know then how much was ended. When I look back now from this high hill of my old age, I can still see the butchered women and children lying heaped and scattered all along the crooked gulch as plain as when I saw them with eyes still young. And I can see that something else died there in the bloody mud, and was buried in the blizzard. A people’s dream died there. It was a beautiful dream . . . . the nation’s hoop is broken and scattered. There is no center any longer, and the sacred tree is dead.”

Duwamish / Suquamish Displacement

The Duwamish People and their neighboring tribes who lived on the land in what is now called Seattle Washington had also been displaced by the government. In 1851, when the first European-Americans arrived at Alki Point, the Duwamish occupied at least 17 villages, living in over 90 longhouses, along Elliott Bay, the Duwamish River, the Cedar River, the Black River--which no longer exists, Lake Washington, Lake Union, and Lake Sammamish according to the Duwamish Tribe website. They were distinct groups of people living in and around the Puget Sound area. Although they shared a single language, other parts of their cultures remained distinct to them such as particular foods and canoe styles. Once traders and settlers became common place, these groups or bands united together and called themselves Duwamish.

|

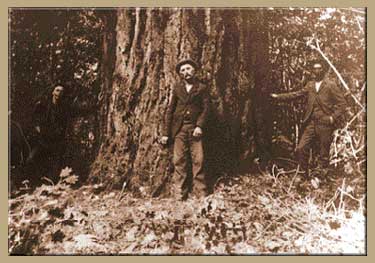

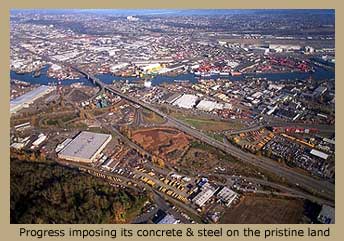

Three men posed in front of one of the huge ancient trees in the area of the present-day airport. They were on a “scouting trip” to this area to see if they could find some good land for a family farm. Imagine the devastation felt by the Duwamish People, witnesses to the destruction of their beautiful land--cutting down huge ancient trees such as this, polluting or filling in waterways, affecting salmon runs. Three men posed in front of one of the huge ancient trees in the area of the present-day airport. They were on a “scouting trip” to this area to see if they could find some good land for a family farm. Imagine the devastation felt by the Duwamish People, witnesses to the destruction of their beautiful land--cutting down huge ancient trees such as this, polluting or filling in waterways, affecting salmon runs.

|

The 1855 Treaty created a Government-to-Government relationship between the United States and the Duwamish. The United States Senate ratified the Point Elliott Treaty in 1859 guaranteeing hunting and fishing rights and reservations to all Tribes represented by the Native signers. The United States Senate ratified the Point Elliott Treaty in 1859 guaranteeing hunting and fishing rights and reservations to all Tribes represented by the Native signers.

In return for the benefits promised in the treaty by the United States government, the Duwamish Tribe exchanged over 54,000 acres of their homeland. Today those acres include the cities of Seattle, Renton, Tukwila, Bellevue, and Mercer Island, and much of King County.

European-American immigrants soon violated the Treaty of 1855, triggering a series of Native rebellions from 1855 to 1858 known as the Indian War. Instigated by the European-Americans, this war set tribe against tribe, and brother against brother. The new settlers also quickly chopped down the trees and interfered with and polluted the waterways.

The Duwamish had been forced from their Longhouses in the new city of Seattle and other parts of their homeland. The United States Army and other Whites set fire to and burned down their Longhouses to prevent the Duwamish from returning to their traditional homeland area.

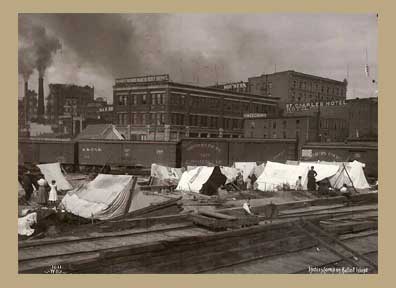

Many Duwamish people did not want to relocate and be forced to live with traditional enemies at reservations built far from their ancestral villages and burial grounds.  For several years, they were allowed to live on the bleak parcel of land called Ballast Island, devoid of fresh water and other vital resources. Located in Seattle harbor, Ballast Island is where ships would dump their ballast. Indians lived on it, and traveled to Seattle by canoe. Later, the natural tidelands south of Yesler St. were filled in--the habitat destroyed, and the Washington St. pier was built on Ballast Island. For several years, they were allowed to live on the bleak parcel of land called Ballast Island, devoid of fresh water and other vital resources. Located in Seattle harbor, Ballast Island is where ships would dump their ballast. Indians lived on it, and traveled to Seattle by canoe. Later, the natural tidelands south of Yesler St. were filled in--the habitat destroyed, and the Washington St. pier was built on Ballast Island.

The Duwamish adopted the use of canvas tents to replace their traditional cattail mat shelters, shown here.  They became a displaced People--forced off their own land--their homes destroyed by the whites. They became a displaced People--forced off their own land--their homes destroyed by the whites.

In time, even Ballast Island became too valuable to the Whites and the Duwamish were exiled once again. By 1917, at the beginning of World War I, Native Americans living on Ballast Island was a distant memory.

Today, the Duwamish are not recognized as a legitimate tribe by the U.S. government. President Clinton, on the last day of his office, decreed their legitimacy; and, subsequently, President George Bush followed and disenfranchised the legitimate status. Now, the Duwamish are in a position to have to buy back land upon which they had lived for centuries.

Click on the rug to return to the top of the page.

Home Home

Quiz Quiz

About Author About Author

|

![]() ©2015 Lilthea Designs

©2015 Lilthea Designs